Fik van Gestel

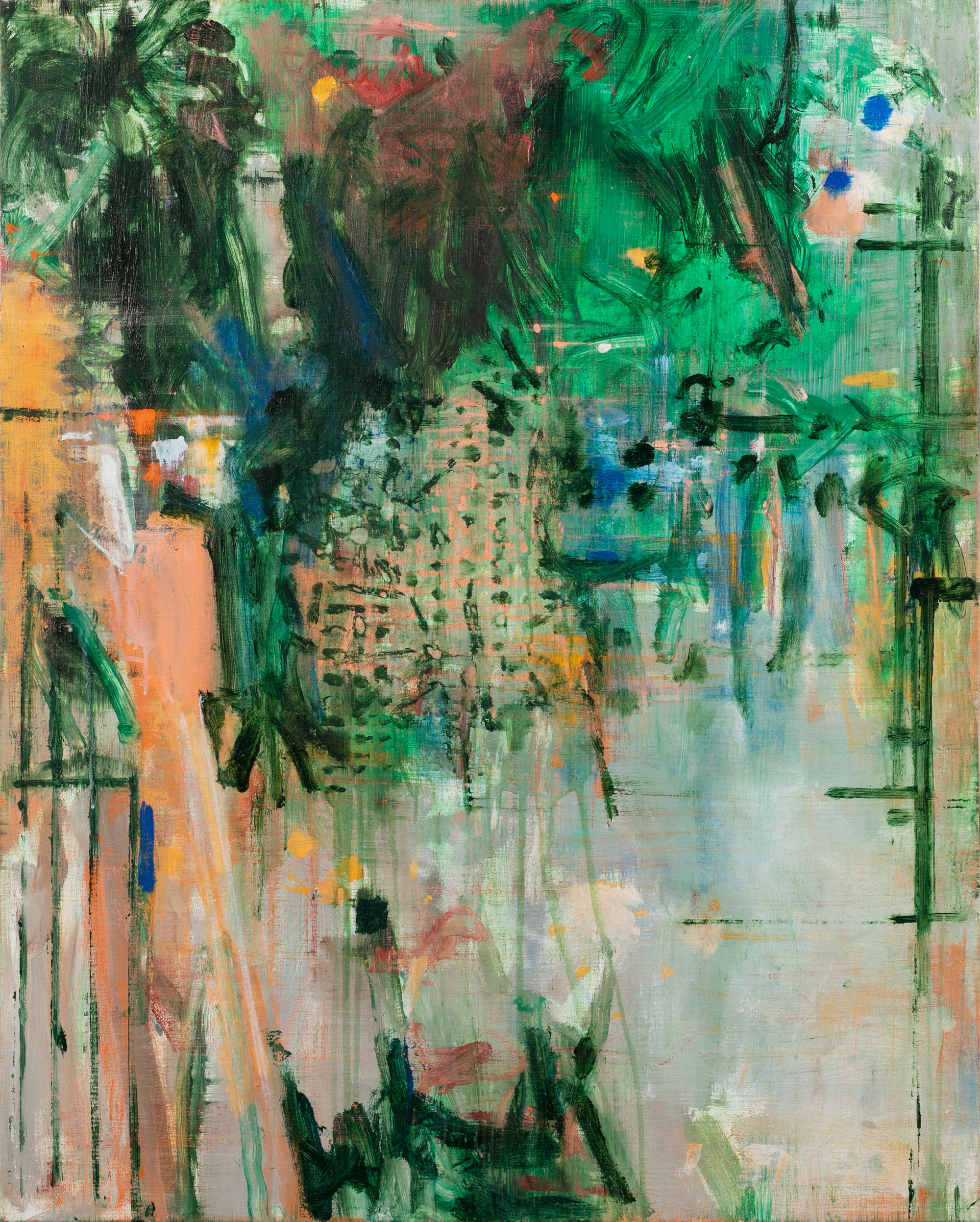

Voor de knoppen

08.03.2020 - 27.06.2020

Primal Force

‘Il ne s’agit pas de peindre la vie. Il s’agit de rendre vivante la peinture’

Pierre Bonnard

During the last fifteen years of his life, Léon Spilliaert mainly drew and painted trees. In his beloved Indian ink, sometimes supplemented with gouache, he created silhouettes of mainly naked trees: a fine pattern of branches, somewhere in between surrealism and symbolism. I suspect he mainly wanted to show that he was in the winter of his life. Or, more generally, he wanted to sketch a picture of 'la condition humaine', the human deficit: mankind as a graceful but barren tree. Call it: metaphysical drawing.

One tree is not like the other. Not in nature, nor in the visual arts. Fik van Gestel also has a thing for trees, just like Léon Spilliaert, but his relationship to the tree is of a completely different nature, if you will forgive this pun. Fik also paints his trees completely differently.

For Fik van Gestel, the tree, and by extension the whole of nature, is a symbol of life force. The tree is vertical. The tree is like a spine. A tree rises. There is the proud crown, which hangs full of foliage in spring and summer. The structure of the crown mirrors, as it were, the root structure with which the tree has anchored itself in the ground and from which the juices are pumped up.

Moreover, the tree is one of the most visible messengers of spring and autumn, of change but also of the reassuring return of the same that is always different: spring comes after winter. Always. Decline and death, autumn and winter may be an integral part of 'the rhythm of the seasons', but they are not part of the pictorial universe of Fik van Gestel. Even though he paints a bare tree, the tree always stands for energy and vitality, for what singer and writer Wannes Van de Velde once so captivatingly called 'the rampant vitality of plants and animals and people'.

It can hardly come as a surprise that Fik van Gestel is a great admirer of Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947). The French painter is a colour magician, just like his friend Henri Matisse. But unlike Matisse, who works with large areas of colour, Bonnard paints with short brushstrokes, making his works blaze with colour. His colours glow as if he were painting an intensified reality. Yet his paintings breathe a benevolent tranquility: they are often lush landscapes, unbridled nature in which man may be insignificant but at the same time enjoys. It is Bonnard's version of Arcadia or the earthly paradise.

Fik van Gestel draws inspiration from Bonnard in works such as 'Balkon' (Balcony) and 'Le jardin de Pierre', but resolutely goes his own way. In 'Le jardin de Pierre' he lets the paint curl, shimmer and grow rampant. Sometimes he allows his paint to leak and drip off the canvas, sometimes he applies it fully and creamy. The colours - yellow, orange, brown, green - shine, they are vivid, bright and warm. In some places there is a hint of organic forms - a tree trunk, flowers and leaves - but they are hardly more than fragments and shades. ‘Le jardin de Pierre' is an atmosphere, a gathering of colours in search of a form.

At the bottom right Fik Van Gestel has painted a fairly large batch of turquoise. It looks like a pond in which lights or stars are reflected. But that is perhaps too figurative an interpretation of a painting that moves on the boundary of abstraction and in which the main role is played by swift brushstrokes and paint that is full of constrained energy.

'Balkon' refers to 'Le balcon à Vernonnet', a 1920 Bonnard painting. It was an inspiring starting point for Fik van Gestel. If you compare the two paintings, you will notice how Bonnard provided a structure and a colour pattern. But at a certain point Fik van Gestel let go of the example and – call it a ‘pre-view’ – gave free rein to his own creativity. Only the structure and a few colours still remind us somewhat of Bonnard's original: on the left the railing of a balcony, in the middle of the garden a blossoming apple tree and at the back a green screen of trees.

Fik van Gestel puts this painting under tension through the use of contrasting colours and the way in which he applies the paint. In 'Balkon' he sometimes applies the paint tightly and rectilinearly (e.g. the grid on the left) or he lets it swirl and crawl. This creates an exciting interplay between stripes and dots, between expanding stains and a structured firework of brushstrokes, between tautness and proliferation, between form and chaos. The vivid touches of paint in bright yellow, blue and orange provide extra depth to the composition.

'Balkon' is an opulence of colour and paint, which, in terms of sensation, is close to nature's unbridled life force. As if a forest, a garden, trees, bushes, flowers and grass, all together have become paint.

There is even more tension in a remarkably powerful painting like 'Nete IV', where Fik van Gestel painted a grid of yellow and orange against a stormy background in blue, purple and black. These complementary colours create a rich contrast and at the same time there is the heightened tension between the amorphous background and the taut stripes, which in turn depict a kind of cartoon-like explosion. As if a big bang in paint has just taken place. 'Nete IV' is materialised energy.

That primal force also lies, in my opinion, in the series ' Afspraak' (Appointment). Fik van Gestel says that he was inspired by the decor of the programme with the same name on the VRT television station Canvas. But I see nothing less in it than an exploration of the earliest, prehistoric animal paintings, as we know them in the cave of Lascaux. As if Fik van Gestel chooses a primal experience in those paintings too: he depicts the silhouette of animals in a very simple, almost naive way.

Similar pure, seemingly simple patterns of powerful, even brutal paint strokes can be found in 'Wachten' (Waiting) and 'Voor de knoppen V' (Before the buds V). Behind the grid pattern in the first painting lies a mathematical formula and an exploration of the limits of the canvas; in the second work Fik van Gestel has reduced the tree to its essence: a trunk and bare branches, almost a skeleton. The tree is a structure of paint strokes, both figurative and abstract at the same time. The monumental painting rather depicts the ‘tree’-idea.

The tree looks like a pure pretext to paint: tight, austere, potent and cheeky. As a much-needed contrast, the painter introduces playfulness with a few colours. Notice how here as well the painter brings depth and tension into the canvas with a few red vertical stripes.

Moreover, 'Voor de knoppen' is one of those witty and titillating titles that Fik van Gestel gives to his paintings. The painter likes puns and neologisms. ‘Voor de knoppen’ (Before the buds) refers to the period before spring, before the blossoming of the trees. But of course there is also the wink to the Dutch expression 'naar de knoppen', which means ‘broken’. The preference for such titles links him to that other painter he admired, Raoul De Keyser, who gave his paintings equally clever and sophisticated titles.

A painting arises while it is being painted. That seems a nonsensical statement, but Fik van Gestel does not always have a preconceived plan and if there is one, it is constantly adjusted along the way and is subject to sudden ideas, slips and accidents, all of which turn out to be productive in themselves. Working on a single painting can go quickly, but it can also be slow. It can be a struggle, spread over years. Rejected work - Fik is very critical - is put away and perhaps later, much later, overpainted and receiving a new final destination. Through the layers of paint, paintings show their (pre)history here and there.

Another constant in the work of Fik van Gestel is the energy. In each painting, the primal force lurks dormant, the 'lust for growth' as a striking figurative work is called. The 'hand' of the painter is always present. That hand can scrape and wipe, be fierce and hard, but also love and caress, polish away and overpaint. This pictorial power of Fik van Gestel can be found in monumental work, but just as much in smaller paintings.

It is invariably painting as a trial of strength. The painter struggles with his paint, restrains it, cherishes it, touches it and kneads it. Each canvas is like a field, a farmland or a garden. And the painter paints trees, in his image and likeness.

Eric Rinckhout

‘Il ne s’agit pas de peindre la vie. Il s’agit de rendre vivante la peinture’

Pierre Bonnard

During the last fifteen years of his life, Léon Spilliaert mainly drew and painted trees. In his beloved Indian ink, sometimes supplemented with gouache, he created silhouettes of mainly naked trees: a fine pattern of branches, somewhere in between surrealism and symbolism. I suspect he mainly wanted to show that he was in the winter of his life. Or, more generally, he wanted to sketch a picture of 'la condition humaine', the human deficit: mankind as a graceful but barren tree. Call it: metaphysical drawing.

One tree is not like the other. Not in nature, nor in the visual arts. Fik van Gestel also has a thing for trees, just like Léon Spilliaert, but his relationship to the tree is of a completely different nature, if you will forgive this pun. Fik also paints his trees completely differently.

For Fik van Gestel, the tree, and by extension the whole of nature, is a symbol of life force. The tree is vertical. The tree is like a spine. A tree rises. There is the proud crown, which hangs full of foliage in spring and summer. The structure of the crown mirrors, as it were, the root structure with which the tree has anchored itself in the ground and from which the juices are pumped up.

Moreover, the tree is one of the most visible messengers of spring and autumn, of change but also of the reassuring return of the same that is always different: spring comes after winter. Always. Decline and death, autumn and winter may be an integral part of 'the rhythm of the seasons', but they are not part of the pictorial universe of Fik van Gestel. Even though he paints a bare tree, the tree always stands for energy and vitality, for what singer and writer Wannes Van de Velde once so captivatingly called 'the rampant vitality of plants and animals and people'.

It can hardly come as a surprise that Fik van Gestel is a great admirer of Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947). The French painter is a colour magician, just like his friend Henri Matisse. But unlike Matisse, who works with large areas of colour, Bonnard paints with short brushstrokes, making his works blaze with colour. His colours glow as if he were painting an intensified reality. Yet his paintings breathe a benevolent tranquility: they are often lush landscapes, unbridled nature in which man may be insignificant but at the same time enjoys. It is Bonnard's version of Arcadia or the earthly paradise.

Fik van Gestel draws inspiration from Bonnard in works such as 'Balkon' (Balcony) and 'Le jardin de Pierre', but resolutely goes his own way. In 'Le jardin de Pierre' he lets the paint curl, shimmer and grow rampant. Sometimes he allows his paint to leak and drip off the canvas, sometimes he applies it fully and creamy. The colours - yellow, orange, brown, green - shine, they are vivid, bright and warm. In some places there is a hint of organic forms - a tree trunk, flowers and leaves - but they are hardly more than fragments and shades. ‘Le jardin de Pierre' is an atmosphere, a gathering of colours in search of a form.

At the bottom right Fik Van Gestel has painted a fairly large batch of turquoise. It looks like a pond in which lights or stars are reflected. But that is perhaps too figurative an interpretation of a painting that moves on the boundary of abstraction and in which the main role is played by swift brushstrokes and paint that is full of constrained energy.

'Balkon' refers to 'Le balcon à Vernonnet', a 1920 Bonnard painting. It was an inspiring starting point for Fik van Gestel. If you compare the two paintings, you will notice how Bonnard provided a structure and a colour pattern. But at a certain point Fik van Gestel let go of the example and – call it a ‘pre-view’ – gave free rein to his own creativity. Only the structure and a few colours still remind us somewhat of Bonnard's original: on the left the railing of a balcony, in the middle of the garden a blossoming apple tree and at the back a green screen of trees.

Fik van Gestel puts this painting under tension through the use of contrasting colours and the way in which he applies the paint. In 'Balkon' he sometimes applies the paint tightly and rectilinearly (e.g. the grid on the left) or he lets it swirl and crawl. This creates an exciting interplay between stripes and dots, between expanding stains and a structured firework of brushstrokes, between tautness and proliferation, between form and chaos. The vivid touches of paint in bright yellow, blue and orange provide extra depth to the composition.

'Balkon' is an opulence of colour and paint, which, in terms of sensation, is close to nature's unbridled life force. As if a forest, a garden, trees, bushes, flowers and grass, all together have become paint.

There is even more tension in a remarkably powerful painting like 'Nete IV', where Fik van Gestel painted a grid of yellow and orange against a stormy background in blue, purple and black. These complementary colours create a rich contrast and at the same time there is the heightened tension between the amorphous background and the taut stripes, which in turn depict a kind of cartoon-like explosion. As if a big bang in paint has just taken place. 'Nete IV' is materialised energy.

That primal force also lies, in my opinion, in the series ' Afspraak' (Appointment). Fik van Gestel says that he was inspired by the decor of the programme with the same name on the VRT television station Canvas. But I see nothing less in it than an exploration of the earliest, prehistoric animal paintings, as we know them in the cave of Lascaux. As if Fik van Gestel chooses a primal experience in those paintings too: he depicts the silhouette of animals in a very simple, almost naive way.

Similar pure, seemingly simple patterns of powerful, even brutal paint strokes can be found in 'Wachten' (Waiting) and 'Voor de knoppen V' (Before the buds V). Behind the grid pattern in the first painting lies a mathematical formula and an exploration of the limits of the canvas; in the second work Fik van Gestel has reduced the tree to its essence: a trunk and bare branches, almost a skeleton. The tree is a structure of paint strokes, both figurative and abstract at the same time. The monumental painting rather depicts the ‘tree’-idea.

The tree looks like a pure pretext to paint: tight, austere, potent and cheeky. As a much-needed contrast, the painter introduces playfulness with a few colours. Notice how here as well the painter brings depth and tension into the canvas with a few red vertical stripes.

Moreover, 'Voor de knoppen' is one of those witty and titillating titles that Fik van Gestel gives to his paintings. The painter likes puns and neologisms. ‘Voor de knoppen’ (Before the buds) refers to the period before spring, before the blossoming of the trees. But of course there is also the wink to the Dutch expression 'naar de knoppen', which means ‘broken’. The preference for such titles links him to that other painter he admired, Raoul De Keyser, who gave his paintings equally clever and sophisticated titles.

A painting arises while it is being painted. That seems a nonsensical statement, but Fik van Gestel does not always have a preconceived plan and if there is one, it is constantly adjusted along the way and is subject to sudden ideas, slips and accidents, all of which turn out to be productive in themselves. Working on a single painting can go quickly, but it can also be slow. It can be a struggle, spread over years. Rejected work - Fik is very critical - is put away and perhaps later, much later, overpainted and receiving a new final destination. Through the layers of paint, paintings show their (pre)history here and there.

Another constant in the work of Fik van Gestel is the energy. In each painting, the primal force lurks dormant, the 'lust for growth' as a striking figurative work is called. The 'hand' of the painter is always present. That hand can scrape and wipe, be fierce and hard, but also love and caress, polish away and overpaint. This pictorial power of Fik van Gestel can be found in monumental work, but just as much in smaller paintings.

It is invariably painting as a trial of strength. The painter struggles with his paint, restrains it, cherishes it, touches it and kneads it. Each canvas is like a field, a farmland or a garden. And the painter paints trees, in his image and likeness.

Eric Rinckhout