Deleu/Deprez: displacements, border crossings

Kris Pint

In 2019, at the invitation of the Verbeke Foundation, Koen Deprez had two electricity pylons laid crosswise on top of each other in Kemzeke. The work refers to Luc Deleu's Demonstration of scale and perspective, installation with two high-voltage pylons from 1986, which were two pylons laid side by side across Ghent's Sint-Pietersplein. This intervention was part of a series of exercises of Deleu's T.O.P. Office into scale and perspective, including a collage of gigantic cruise ships at sea and a design for identical tower blocks that could be built both vertically and horizontally.

But in addition - and this was particularly provocative - the high-voltage pylons in Ghent were also an exercise in style, by contrasting the monumental character of modern utility architecture with a baroque abbey church. An early lesson, too, in the necessity of adaptive reuse, especially in a country like Belgium. Luc Deleu had already addressed this topic by laying Belgium’s "Last Stone" in a 1981 performance, because he felt it was overbuilt. Adaptive reuse often focuses on the glorification of the patina, the lived-through, the Japanese wabi sabi that Leonard Koren describes as ‘coming to terms with what you consider ugly.’ But this ‘ugliness’ often remains encased in an Eastern aesthetic, the beauty of the imperfect, the transient. Deleu's exercise makes clear that through the notion of the readymade, one can repurpose much more radically. Deleu's inspiration is not the weathered, distinct Japanese tea set, but rather Duchamp's inverted urinal, now on the scale of a city square. It's the same attitude that in 1985 led him to the idea of reusing an oil rig for a walking pier in Vlissingen. The proposal was perfectly rational - it required no new construction, the height differences and the shape would make it a perfect attraction - and at the same time it was totally alienating, a short circuit between industrial production and tourism consumption. Recycling as a surrealist collage.

Koen Deprez also links the brutal beauty of modern infrastructure and means of transport to an aversion to predetermined functions and conventions. But what Deprez adds to the formula is a latent threat of violence. For example, Deprez's pylon cross is called Accidental Pedestal for Girolamo Savonarola. A reference to the Florentine penitential preacher who so convincingly announced the end of times that the Florentines lit a "bonfire of the vanities" in the Piazza della Signoria, throwing works of art, books, jewels, and other luxury items into the flames, before finally letting Savonarola suffer the same fate there in 1498.

The way in which design inflicts violence to the user is a recurring motif with Deprez, even on the seemingly human scale of living. For example, Deprez designed an impossible tricycle for twins, on which they each cycle in a different direction, with all the future conflicts this entails. In another concept, he constructs living quarters for three men, almost hermetically sealed off from the outside world: the volumes are located within the secure, enclosed grounds of an airport and hardly have any windows. Contact with the outside world becomes almost impossible in this concept, and the difference between voluntary reclusiveness and forced confinement is very thin. Or take the house for Bruno Mussolini, pilot and son of the dictator, whose body was cut in half in 1941 when his plane - a secret prototype - crashed into a house. Deprez's design repeats these forces in his own prototype for a home: an unfinished, open-cut, indeterminate architectural space, in which you still seem to vaguely recognize an airplane wing.

The deadly force of the crash evoked by Deprez is nothing more than an extreme example of the violence that is inherent to the built environment. Through the use of materials, form, but also through implicit and explicit patterns of expectation, every design exerts a compulsion. Deprez's oeuvre expresses sympathy for those who resist, the ones who stubbornly fight the imposed normality, the manual to be followed, the predetermined routes. Yet that sympathy remains distant: Savonarola and Mussolini are not characters with whom you immediately want to identify. With Deprez, the rebel also knows that resistance ultimately produces nothing, is at best a delayed execution. This makes the house for Bruno Mussolini a constructivist heir to the baroque memento mori paintings. Wry tile wisdom: there’s no place like home, even with a ticking time bomb inside.

In comparison, Deleu’s oeuvre has a much more optimistic undertone. Between 1995 and 2004, T.O.P. Office worked on The Unadapted City. No urban fabric can ever accommodate the diverse needs and wishes of all its inhabitants, which makes it all the more important to determine which public functions are a minimal necessity. This was quite a task, and in 1997 architects Steven Van den Bergh and Isabelle De Smet joined the firm. What had until then been a duo, Luc Deleu and his wife Laurette Gillemot, now became a quartet. The best-known result of this study was the model VIPCITY – Zeemijl, a design for a linear city one nautical mile long.

For Deprez, the problem lies deeper: not only the city itself, but human behaviour as a whole is fundamentally inappropriate. Against the utopian linear city, he placed the design for an aggression park in 1984. The public space becomes a garden of discord: an abstract sequence of spaces in which the users are at the mercy of each other's impulses.

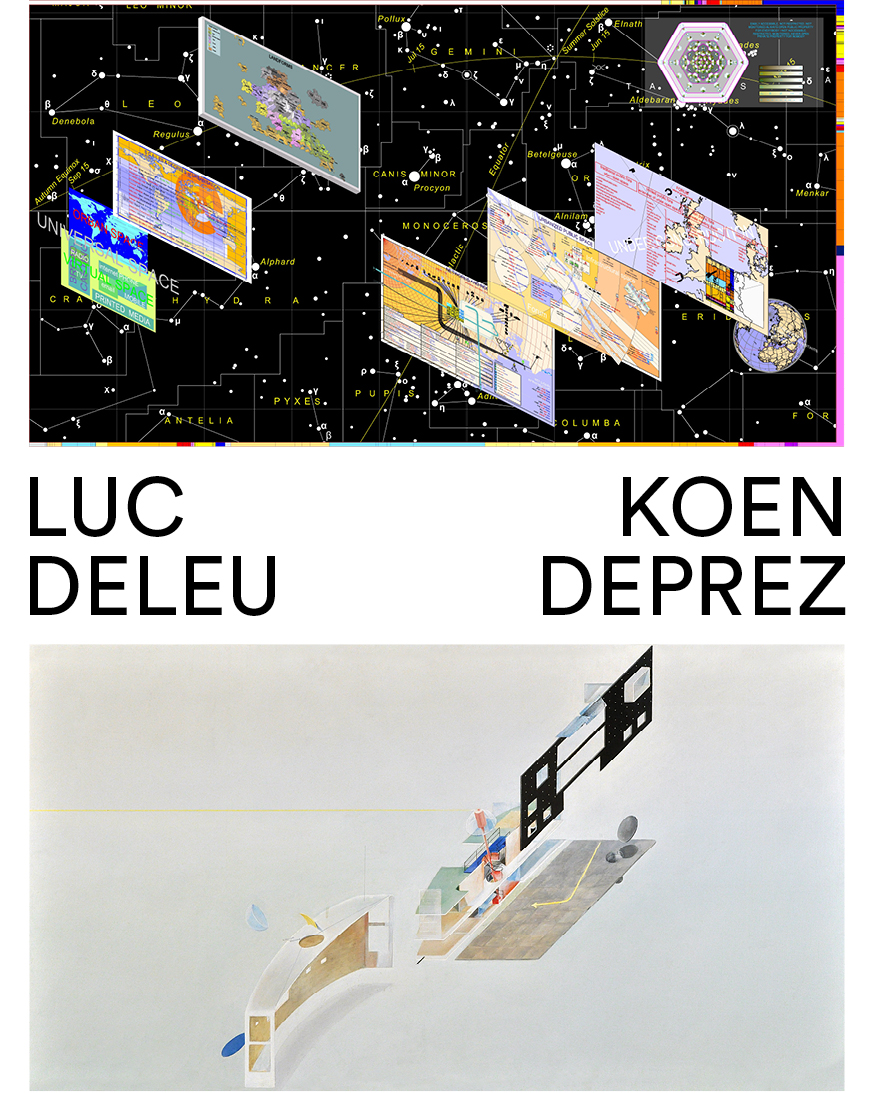

This different view of the human condition recurs at every scale of their thinking, including the largest imaginable: the representation of the world. With Deleu the world becomes a 'spaceship earth', after the famous notion with which R. Buckminster Fuller made it clear that viewed from space we are all in the same boat. Hence Deleu's plea for 'orbanism': designing on the scale of man demands designing on the scale of the world because everything is interconnected. This is also why in 1972 Deleu proposed housing a new campus for the University of Antwerp on three aircraft carriers. Another exercise in perspective, this time not visually, but intellectually. It wanted to teach students and the faculty to think and work on a global scale. The project was obviously not realized, but years later Deleu would still put this basic idea into practice with the ‘tours’ of the Mobile Medium University, sailing around the world on sailboats and cargo ships.

For Deprez, too, ships symbolize knowledge, and travel and learning are related. His ships are given the names of thinkers and artists who have inspired him: for example, one of the ships is called Deleu/T.O.P.-office. But these ships are not part of a university, they form a war fleet. Deprez conceives his oeuvre as a nautical map, scattered with bullet holes and craters. The learning process here consists of conflicts, including with oneself, in which, above all, much must be unlearned. For Deprez, a school is not an aircraft carrier, but has the Tower of Babel as a symbol, after an illustration from Anasthasius Kircher's book of 1679. Deprez turns the tower upside down, like a blunt drill which, on its way down, drags along all the language games with which we give meaning to the world. Deleu puts down the high-rise, Deprez tilts it even further, deep below the surface. The lighthouse, a classic symbol of enlightenment, is so deep beneath the waves that it can only serve as a buoy, while the lighthouse keeper is condemned to a house without light. For Deprez, the image of the spaceship does not express solidarity either. It is stranded in the wrong place, at the wrong time. Its devices are reused as melancholy beach cabins, a refuge for misplaced aliens.

And yet the division between Deleu as a utopian and Deprez as a nihilist is far too simplistic. After all, there is also something unspokenly violent in Deleu's blending of the modernist rationality of Le Corbusier with the surrealism and revolt of the 1960s. 'A proposal for more confusion' is what Deleu sprayed on the sidewall of his house, and that also sums up the premise of his 'urbanist art'. Terms like VIPcity, orbanism, but also the name T.O.P. (Turn-On Planning) Office itself, just like the logo of the upside-down globe, parody the pompous jargon of study and design firms. And at the same time, it is anything but casual irony. The sowing of confusion is always done with an eye to the future: the seemingly playful and provocative 'proposals' from 1972, such as those for urban wildlife, high lawns, and the protection of weeds, suddenly acquire a lucid, ecological urgency decades later. And conversely, Deprez's oeuvre also has something utopian and even comforting, albeit in a subdued way. Many architectural and urban planning visions desperately ignore the negative aspects of existence: unrest, alienation, fear, aggression. Demons become fierce if you don't give them a place. And precisely because Deprez is able to translate them into architecture, it becomes possible to trace counterforces and lines of escape.

The strange kinship between Deleu and Deprez is, in my opinion, also evident in the latest project of T.O.P. Office, Darling Springs, both final piece and eternal work in progress: an imaginary urban layout that should do away with ad hoc urbanism. It is an attempt to represent public space on a global scale, the Unadapted City embedded in a grid of all possible landforms on earth. This training ground for future urban planning artists suggests the phantasm of the perfect structure, in which every element has a place, can move freely and can be reshuffled and rescaled again and again. It offers an order that at the same time implies radical freedom, for its concrete architectural realisation remains open. As an ironic counterpart to this project, there is Deleu's maquette, based on the row of prototypes of pieces of the border wall then-President Donald Trump wanted to erect on the southern border of the US. Together, these full-size prototypes form a monumental ready-made, unwanted land art with a wry political message. A message completely opposite to Deleu’s, whose containers and pylons just emphasize the mobility of the modern, a mobility against which the myth of the wall no longer stands. The urbanism of the future will have to offer protection and structure in a different way, without succumbing to the authoritarian temptation of expert planners who impose their will. The choice of the somewhat kitschy name Darling Springs, as if coined by dodgy property developers, makes it clear that this is a promise to be taken both seriously and distrusted.

Darling Springs resembles Deprez's series of Annunciations, in which Deprez copies a series of works by old masters, turns them upside down, and then covers them with white titanium paint and gold leaf. This obliterates the theme itself, the announcement of Christ's birth to Mary by the archangel Gabriel. But at the same time, it creates an abstract pictorial space in which something remains imminent - a fruitful intrusion into the mundane, the promise of radical change. The same is true of the pictorial space of Darling Springs: to arrive at the actual work - the future city for Deleu, the original painting for Deprez - you have to scratch, reject the gold leaf, scrape off the white and dare to make a mess.

When Deprez and Deleu met in Kemzeke, there was a safe buffer of time and space. In this double exhibition, that buffer disappears, and the imaginary spaces evoked by their work inevitably flow into one another. Border controls are pointless. Characters flee Deprez's frenetic landscape, choose the most beautiful border wall to blow up, and without official documents, they then intrude into Darling Springs. There, grateful for the empty, white space, they fill their days with lawful and unlawful acts. In a game of perspective and scale, their crimes are simultaneously too big and too futile to be detected by the authorities. And conversely, Deleu's cheerful anarchism also blows into Deprez's space. In the beach cabins plans are forged for the ideal city, and someone cheerfully sprays graffiti on the austere volumes: 'underneath the pavement, the beach, the weeds, the swamp: … the world.'